Beethoven’s Eroica

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55 — better known as the Eroica — is one of the most renowned and monumental works in the history of musical creation. This titanic composition opened the door to a new artistic path and demonstrated that music can be a powerful reflection of the social turbulence of its time and a composer’s response to an extramusical stimulus. That stimulus was — Napoleon Bonaparte. His presence looms over every page of the symphony, yet like many other intellectuals of the early 19th century, Beethoven felt profound disappointment when Napoleon crowned himself Emperor. The inscription “Sinfonia Bonaparte” was removed and replaced with a more neutral one: “Heroic Symphony to celebrate the memory of a great man.”

In 1802, confronted with the increasing loss of his hearing, Beethoven wrote a document that would later become known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, named after a Viennese suburb where it was composed. In it, the composer confessed with painful honesty his altered physical and emotional state. Later in his correspondence, Beethoven noted that he was seeking “a new path,” one that would reflect his inner condition and help him transcend it. This new path led him beyond abstract music and toward programmatic writing — not in the Romantic sense of storytelling (as in Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique), but in the sense of infusing the very musical fabric with emotional charge and lived experience.

With the opening two E-flat major chords of the symphony, Beethoven becomes a new man — and the creator of a new musical direction.

After those two cannon-like strokes, the cellos introduce a theme that appears to be the main subject. However, the first movement is not built upon a single central idea. By measure 85, four distinct thematic units have already been presented, with more fanfare-like moments than in any symphony up to that time.

The second movement, a funeral march, as critic Paul Bekker writes, “conjures the feelings of one who watches a funeral procession from afar as it passes and gradually disappears in the distance.” The dazzlingly swift and dynamically nuanced Scherzo marks the return of vitality, while the Trio presents a brilliant showcase for the horn section. It is here that, as Donald Francis Tovey observed, Beethoven fully realizes “Haydn’s desire to replace the minuet with something equal to the other movements of a great symphony.”

The Finale reveals a titan (perhaps Beethoven himself) reborn once again. The opening bars are connected to one of the composer’s favorite themes, previously used in The Creatures of Prometheus ballet, the Piano Variations Op. 33, and a Contredanse. The complete exposition of the theme — in which something seemingly trivial becomes solemn and exalted — is followed by an exciting motif of relentless, heroic character.

The symphony concludes, fittingly, in a blazing triumph.

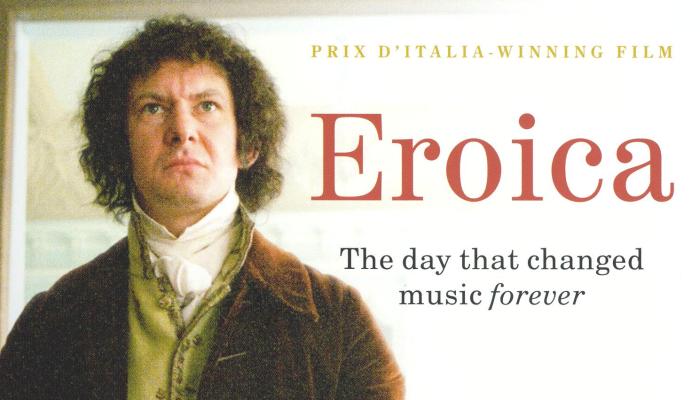

Eroica was first performed in 1804 at a private concert in the Vienna residence of Prince Lobkowitz, and this significant musical moment was dramatized in 2003 in a BBC-produced film directed by Simon Cellan Jones. The Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique is conducted by John Eliot Gardiner, while Beethoven is portrayed with spirited wit and vivid expressiveness by actor Ian Hart.

The appeal of this film lies in several aspects. Above all, it focuses on one musical work and the lives of the people who shape it — the composer and the musicians performing it. It offers a glimpse into the era and the way of life within an aristocratic household. Structured in segments, the film allows ample space for viewers to follow the main themes and musical developments through the movements. Moreover, it does not aim to be a historical account filled with precise dates and heroic military achievements, but rather a portrayal of the everyday lives of those gathered in Prince Lobkowitz’s salon — performing and hearing the latest composition of a deaf, eccentric genius who would soon change the course of music history.

Therefore, alongside the invitation to join us on Sunday, November 30th at 8:00 PM in the Novi Sad Synagogue and experience this remarkable symphony performed by the Vojvodina Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Chief Conductor Aleksandar Marković, we would also like to recommend this film — as a valuable look back at the work’s first performance. Should you watch it before the concert, it may deepen your understanding of the symphony; if you choose to view it afterwards, it can enrich your musical experience during future listening.