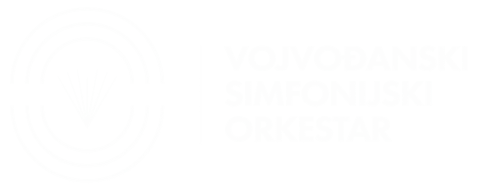

At the Crossroads of Myth and Philosophy – Opera Oedipe

George Enescu (1881–1955) was a Romanian composer, violinist, pianist, conductor, and pedagogue—one of the most versatile musical figures of the 20th century and the most renowned name in Romanian classical music. His exceptional talent was evident from childhood. At the age of seven, he enrolled at the Vienna Conservatory, where he studied violin and composition, later perfecting his craft in Paris under Gabriel Fauré and Jules Massenet. He performed as both violinist and conductor throughout Europe and the United States, and his creative output includes symphonies, chamber music, orchestral, and vocal works. In his unique and authentic style, he combined Romanian folk elements with French impressionism and the German tradition. He gained worldwide fame with his Romanian Rhapsodies Nos. 1 and 2, while his opera Œdipe stands as his magnum opus. As a professor in Paris and Bucharest, he shaped generations of musicians, among whom Yehudi Menuhin and Ivry Gitlis stand out. He lived between Romania and France, and from the Second World War onward, mainly in Paris, where he died on May 4, 1955. He is regarded as the greatest Romanian composer and a singular musical talent of his era.

The opera Œdipe (Oedipus) is a monumental musical and dramatic work in four acts with a prologue, composed to a libretto by the French poet Edmond Fleg, based on Sophocles’ tragedies Oedipus Rex and Oedipus at Colonus. Enescu worked on this composition for more than two decades, between 1910 and 1931. The opera premiered in 1936 at the Paris Opera Garnier, under the baton of Philippe Gaubert. Initially, it received a modest reception, but during the second half of the 20th century, it was performed in Paris, Bucharest, Vienna, and London, and is now recognized as one of the crowning achievements of Romanian culture and one of the most significant operatic works of the 20th century.

Written in French, the opera encompasses the entire life of Oedipus—from his birth and prophecy, through the murder of Laius and his marriage to Jocasta, to his self-blinding and death at Colonus. Its musical language blends the tradition of French impressionism with expressive drama, while elements of Romanian folk tradition lend a distinctive tone to the harmonic texture. The orchestra creates a rich, multi-layered soundscape, relying on monumental choral tableaux and massive symphonic structures.

At the heart of the work lies the psychological portrait of Oedipus—the tragic mythological hero and universal symbol of humanity, who struggles against fate, seeks truth, and ultimately attains serenity and reconciliation. The role, written for baritone, is considered one of the most demanding in the entire operatic repertoire, requiring exceptional vocal power and dramatic focus, along with an almost continuous presence on stage.

The orchestra does not merely illustrate the action but constructs symbolic layers of meaning. Mystical sound masses in the prologue foreshadow the prophecy; the dramatic chords of the Sphinx scene evoke tension and fear; while the luminous harmonies of the final act convey a sense of peace and transcendence.

The chorus occupies a central dramaturgical role, recalling the function of the ancient Greek chorus but in a new, modern form. At times, it represents the people of Thebes; at others, it becomes an abstract voice of destiny or divine will. Its sonic presence builds monumental scenes—from the plague in Thebes, through solemn invocations of the gods, to the people’s rejoicing after the Sphinx’s defeat—before retreating into a calmer tone in the finale, reflecting Oedipus’s reconciliation with his fate.

Oedipus stands as a synthesis where myth and philosophy, tragedy and hope, suffering and reconciliation converge—a fusion of ancient tragedy and modern musical dramaturgy, of impressionistic color and expressionistic intensity, of national folk idiom and universal philosophical message. This very complexity makes it one of the most monumental and profound achievements in 20th-century operatic art.

Synopsis

Prologue – The Prophecy

In the palace of Thebes, a son is born to the royal couple Laius and Jocasta. The oracle reveals a terrible fate: the child will kill his father and marry his mother. To avoid this destiny, the parents order him to be abandoned in the mountains, but a shepherd spares him and delivers him to a shepherd in Corinth.

The music begins with dark tones in the lower registers, evoking mystery and the inevitability of fate. The modal harmonic language and the solemn chorus, the voice of prophecy, build tension between royal dignity and tragic foretelling, shaping the unfolding of the opera.

Act I – The Murder of Laius

In Corinth, Oedipus grows up believing he is the son of King Polybus and Queen Merope. When he learns he is not their child, he goes to Delphi in search of the truth. The oracle reveals a dreadful destiny: he will kill his father and marry his mother. Fearing he might harm Polybus and Merope, Oedipus leaves Corinth. At a crossroads, in a violent confrontation, he kills a stranger—his real father, King Laius.

The music of the first act is marked by sharp rhythms and tense orchestration, reflecting Oedipus’s inner struggle and his fateful journey to Thebes. The encounter with Laius is composed with strong chords and rhythmic strikes—a musical symbol of the father-son conflict. The moment of murder brings a brief but terrifyingly intense climax to the sound drama.

Act II – The Sphinx and the Marriage to Jocasta

Thebes is under the curse of the Sphinx, who kills anyone who fails to solve her riddle. Oedipus succeeds and frees the city. The Thebans hail him as a hero, offering him the throne and the hand of the widow of King Laius—Jocasta. Unknowingly, Oedipus fulfills the prophecy: he becomes the husband of his own mother.

The musical highlight of this act is the Sphinx scene: a ghostly atmosphere shaped by dissonant chords, glissandi, and dark tones of the wind instruments. The alto voice of the Sphinx rests on leaps and shadowy effects, while Oedipus’s solution brings musical clarity and light. Following this, the chorus of Thebans exalts in a festive celebration, and the lyrical duet between Oedipus and Jocasta, in contrast to the dramatic scenes, provides a moment of melodic warmth and apparent calm.

Act III – Discovery of the Truth and Exile

Years later, Thebes is struck by a plague. The oracle declares that the cause of the disaster is the unresolved murder of King Laius. In the search for the murderer, Oedipus increasingly uncovers the truth of his origin. Shepherds reveal the terrible reality: he is the son of Laius and Jocasta. In despair, Jocasta takes her own life, and Oedipus, aware that he has fulfilled the prophecy, blinds himself and goes into exile.

The music of this act most intensely depicts tragedy. The sounds of the plague in Thebes are shaped by dissonant structures and rhythmic strikes of the chorus and orchestra, creating an atmosphere of panic. Oedipus’s search for the truth brings introspective moments in the dark colors of strings and winds, with fragmentary solo lines. The revelation of the truth culminates in a joint sonic climax of chorus and orchestra, while Jocasta’s despair echoes in sudden melodic gestures. Oedipus’s blinding is accompanied by an explosion of dissonance, followed by silence and the somber music of his departure into exile.

Act IV – Peace in Colonus

Blind and exiled, Oedipus wanders with his daughters Antigone and Ismene until he reaches Colonus, near Athens. Under the protection of King Theseus, he finds peace and serenity. Death comes not as an end, but as liberation and reconciliation with fate, turning him into a symbol of human struggle and dignity.

The music of the final act takes on a different, more transparent character. The orchestra moves into bright harmonies, colored by gentle tones of strings and woodwinds. The atmosphere is contemplative and calm. Antigone’s voice brings lyricism and warmth, while the chorus ceases to be a voice of judgment and becomes an echo of the metaphysical space in which Oedipus finds peace.

At the moment of his death, the orchestra rises into an enlightened soundscape: dissonances resolve into open chordal structures, creating a sense of transcendence. Death is not portrayed as a tragedy, but as liberation—a musical symbol of man’s reconciliation with the eternal order.

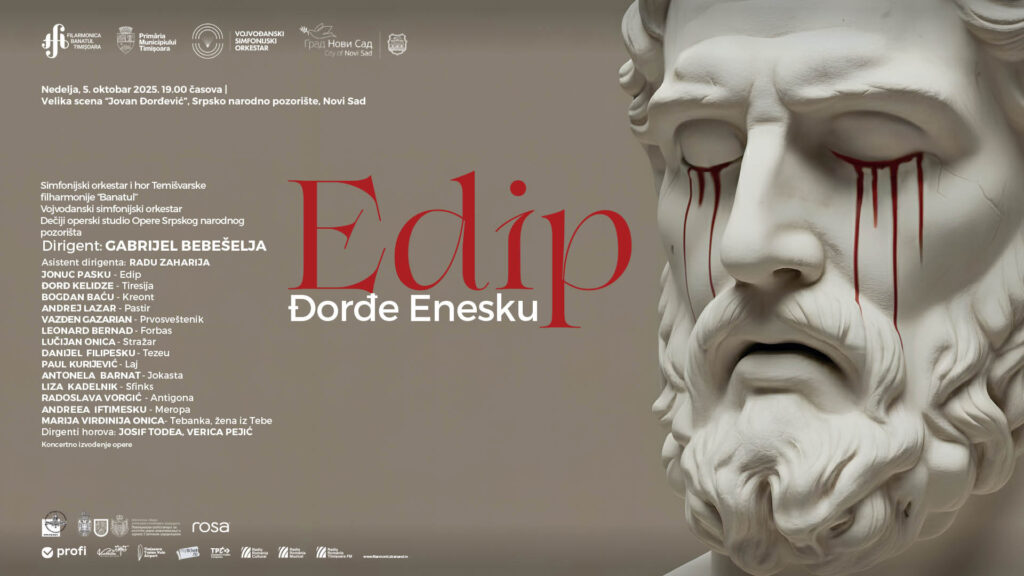

The concert performance of George Enescu’s opera Oedipus will take place on the Grand Stage “Jovan Đorđević” of the Serbian National Theatre on Sunday, October 5, 2025. The performance is realized in accordance with the Cooperation Protocol between the Timișoara “Banatul” Philharmonic and the Vojvodina Symphony Orchestra.

More information about the conductors’ and soloists’ biographies can be found via the QR code.